Deceased in 2009, this great lady of judo and world sport, is unfortunately no longer there to tell us about all the obstacles she had to overcome, but her daughter, Jean, took over and she is inexhaustible when talking about her mother. After an hour of interview, she asks you if you have any questions. It turns out not, because she has already said it all.

It must be said that Jean is currently working on the writing of Rusty's memoirs, which will soon be published, “It was a promise I made to her. When she left us, at only 74 years old, I told her that I would take care of my dad, finish my PhD and make sure her memoir is made public. She had her own way of explaining things and that's what I'm trying to do by transcribing her words."

Guardian of the 'Kanokogi temple,’ Jean likes to remember that she was almost born on the tatami, “Rusty's gynaecologist was one of her judoka students, so from my birth you can say that I knew what Judo was!" She’s smiles. “Above all, what is important is to know that sport needs people like her, again and again. She had an incredible ability to instill self-confidence, encouraging everyone she approached, to make them realise that even when everything is going against you, you have the power to change the world.”

Rusty, after a difficult childhood and youth, had totally embraced the values of judo, to make it a lifeline from which she would never stray, “As soon as you would step on the tatami, you were in an extended part of the family. There was no colour, no gender, just judoka. It was amazing. You could be thrown, even choked, but in the next moment she was hugging you. She was very attached to respect, to the principles of judo and she had a lot of humour."

Jean remembers a day when, practising with Rusty, she relaxed and on a ko-uchi-gari, a little too heavy, her mother sped straight on the wall and went through. Her father had no choice but to laugh, “And now I'm going to have to fix the wall too,” he added.

Before being the organiser of the first Women's World Championship, Rusty was therefore an emerita of judo and a recognised coach, “She believed in old training methods that had been proven. She was hard at work and we trained hard, but it was for our good. Everyone who has passed through her hands knows and recognises it. One day we were in Louisiana for a competition. To get us used to the local climate, she cut the air conditioning and we trained in those conditions. It was horribly hot, but at least we knew what to expect."

Very young, through the teaching and the experience of her mother, Jean learned what frustration and discrimination were, “She explained to us what she had been through and all these trials undeniably forged her character and gave her the motivation she needed to knock down mountains. When my mother was young, there was, said tongue in cheek, a good 'old boys’ network' mindset, that didn't make it easy for women to get into sport. Someone once asked her if she was not afraid for her 'private parts' by practising judo. Her answer was dazzling and perfectly in line with her honest character, 'I think it is the men who must fear more, because, their private parts are outside!' That was Rusty and that's why we loved her so much."

Beyond her outspokenness, Rusty was a woman of conviction, whose line of conduct could not be warped or diverted, “She had a goal in life, to show that equality has no borders. She learned all that by herself. She funded everything; her ultimate dream being to see women's judo enter the Olympic Games. She fought for it and she never gave up, until she won."

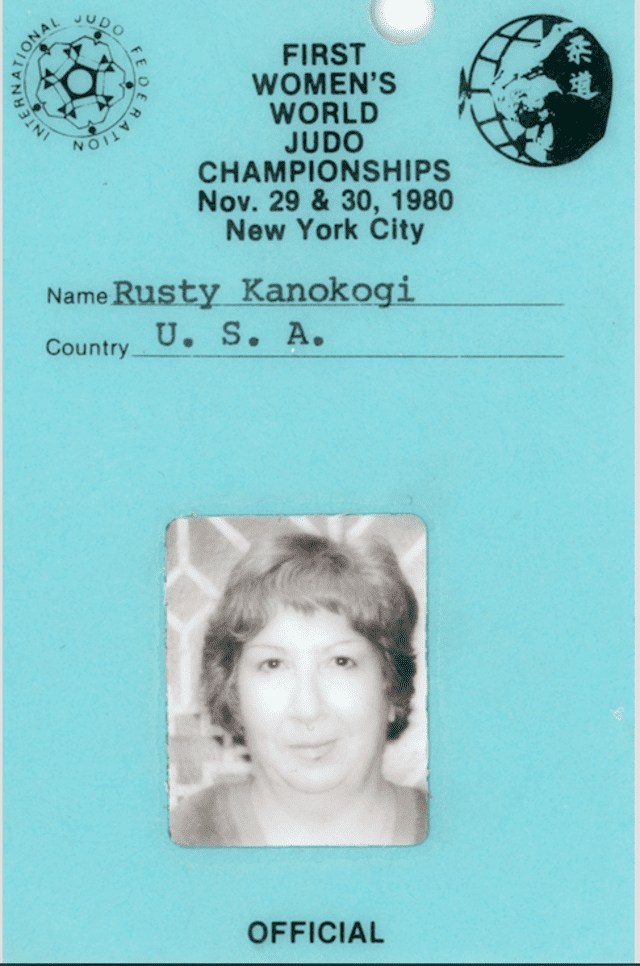

The Kanokogi family, at the end of the 70s, were part of the middle class of the United States and Rusty therefore had to scramble to raise the necessary money, in the necessary time, to organise the championship in New York, “She needed a venue and competitors. For the world championship to be recognised, it had to bring together 25 countries. At a time when the internet did not exist, she succeeded in bringing 27 delegations together. She transformed our house into the headquarters. If you had the 'misfortune' of being nearby, you would find yourself enlisted in the organisation.” Jean laughed, “Not many people believed in her, but she did not give up. Everyone had to make sacrifices. Delegations crowded into hotel rooms and at home we ate sweets for six months. I worked with Rusty and for Rusty, babysat my brother and still went to school. She was always in a meeting! She never rested and during the competition she also did the commentary."

At only 14 years old, Jean found herself enrolled in the organisation of the worlds, “I took care of the press conferences. I wrote letters and during the opening ceremony I carried the USA sign. I was so proud. Later I also became a member of the US team. That was unbelievable."

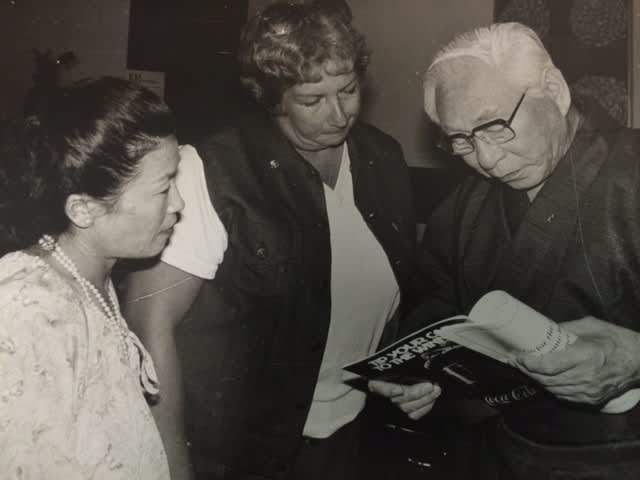

Despite Rusty's best efforts, a few days before the start of the event, the money was still lacking, “This is where the IJF came in. The President at the time, Matsumae Shigeyoshi, arrived in New York with the missing amount of cash. My mother could not believe it. She kept the money at home overnight and the next day she went to deposit it in the bank. Frankly, I wouldn't have wanted to be the one who might have dared to steal that money from her. With her skills in judo and the little sleep she had and all the excitement, he would have had a bad time. Luckily everything went well."

The IJF support was crucial and made it possible to organise the championship under the best possible conditions, “Rusty had doubts about Matsumae-San before, but she would repeat regularly thereafter, that she was totally wrong and he became a close family friend. Our bond with him also explains the bond that we subsequently had with the University of Tokai and with Mr. Yamashita."

1980 therefore marked an important step for Rusty, who was still dreaming of seeing women's judo at the Olympic Games. After the 2nd world championships, held in Paris, she firmly believed in it, “Yet in 1984, she was told that women's judo won't make it to the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. It was like a punch in the face. She wanted to stop the Games. She started legal proceedings. It turned out that there was little chance that these remonstrations would succeed, but the lines were starting to shift. She said that no matter what, a woman had the right to be told she was an Olympic champion. As giving up was not an option, she continued to fight. She looked for all the competitions where she could enter women and each time she found the funding to take a team to prove that it was possible."

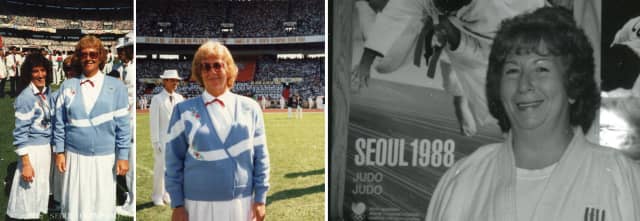

In 1988, women's judo became a demonstration sport, at the Seoul Games and four years later it became a compulsory sport in Barcelona. Rusty was then a coach, “She had never been able to participate as an athlete. There, she did so as a coach. Really, seeing the women on the tatami in Spain was her gold medal. She had succeeded!"

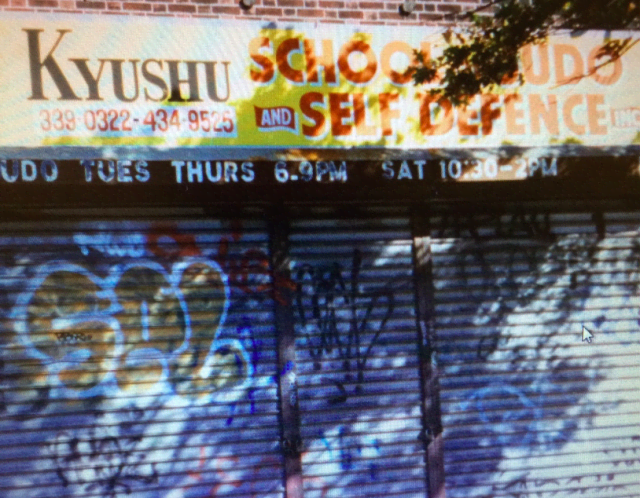

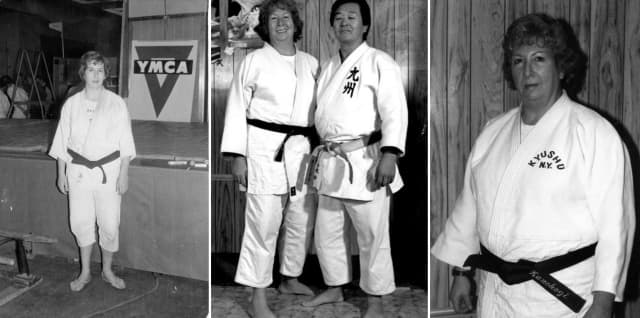

To explain this flawless will, we must remember certain stages in Rusty's life, “She was a difficult child, always ready to get into trouble. When she discovered judo, she fell in love with it. Seeing little guys beating up big guys impressed her. She started practising just with sweatpants and a rope for a belt. She was not allowed a judogi.

When there was that famous competition organised by the YMCA and she won by ippon against a man, the organisers came to see her and asked her ‘Are you a girl?' She said, 'No, I'm a woman.' She didn't get her medal. She was angry and she was in pain and vowed to do everything to make sure that it would never happen again. She was a competitor at heart. She proved it too, when she went to the Kodokan and did everything to train with the men. After 1988, finally, she could relax."

In 1996, Rusty was referee in Atlanta and then coach again in 2000 in Sydney, while in 2004 in Athens, she was a TV commentator, “In 2008, she was too sick to go to Beijing but she was decorated by the Emperor of Japan and in 2009, three months before she passed away, she finally received her YMCA medal, the one she had not received decades before. While receiving it, she thanked the organisation, but added that it should have never been that way. She fought to the end."

Rusty's journey is undoubtedly one of the most exceptional in the world of sport, “She has touched and changed the lives of thousands of women around the world and more generally of everyone she has met. You could be a stranger in the street and overnight you had a family. That's how I was raised. That's what she left to us. She was my mother, but she was also the mother of women's judo and of equity. Today, therefore, I feel that I am the daughter and it is up to me to bring to life the values she instilled in us. Celebrating the 40th anniversary of New York 1980 is to shine the light. The excitement is contagious. It's amazing when I see the testimonials coming from all over the world. It's positive and it's so helpful as the world has been hit by Covid-19. I'm really proud of her and of us, we can all be."