The cadet age category is the first point of contact of significance internationally, where skills are pitted against alternative skills and where gaps in development can be seen clearly and in context. Although it can be argued that the cadet stage does not necessarily translate to results at senior level, it is certainly an encyclopaedia of important learning, gap analyses, technical and tactical honing, relationship-building and target-setting, a stage of great significance on the whole, regardless of individual wins and losses. The names may not be important; here it is the shape of the future of judo that is in view.

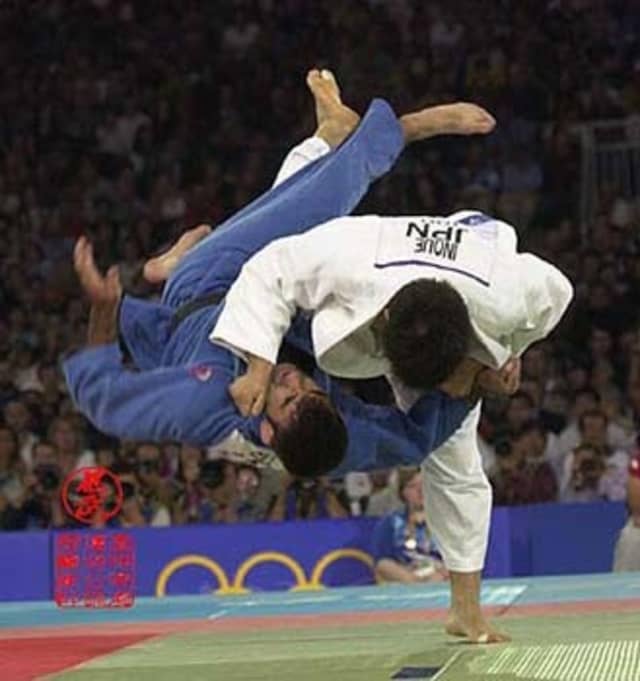

Many years ago I heard Keiji Suzuki (JPN), 2004 Olympic champion, talking about his goals and his drive to practise and perfect uchi-mata particularly, as he saw it as the true essence of perfect judo. He also spoke of the knowledge that to attain absolute perfection is impossible but it would always remain his target, nonetheless. Not to strive for it was to not really live.

Uchi-mata is the favourite technique of many spectators and is also the source of inspiration and aspiration for young judoka, with their gaze firmly set on the likes of Kosei Inoue, Shohei Ono and a host of others. These 3 names alone, Suzuki, Inoue and Ono, hold 4 Olympic golds and 8 world championship golds between them and each developed uchi-mata as their tokui-waza. Their versions were studied and strategised against but their level of practice and testing undertaken gave the opposition little chance.

In Porec, at the European Championships for Cadets, we have been served a glimpse of the future and as always there are a number of judoka working to perfect a rudimentary uchi-mata. In fact, some are not so basic at all and just require fine tuning and consistency against a range of resistance. It was certainly not the most popular scoring technique, but to see teenagers arriving at their biggest game to date with the courage to try such a technical throw, is exciting. They have power and heart and no doubt many of them will collect big ippon wins in the future with it, maybe on the World Judo Tour or at an Olympic Games.

Experts in education and skill acquisition might offer us statistics such as needing 10,000 hours of dedicated training or 10, 000 repetitions of a single skill before it becomes ingrained, becoming an automatic response to a given situation. These cadets are building those hours and every single test of their development, such as a quarter-final in Porec or a strong randori in Valencia, feeds their understanding of success and drives the direction of the file that takes the rough edges away. These uchi-matas are not Inoue’s but they are magnificence in the making.

To perfect oneself in the pursuit of excellence and eventually contribute something to the world remains the goal. Some of these cadets understand it while many will learn later that their practice is more valuable than the simple act of technical development; they are choosing the difficult path of failure and defeat because they already strive to achieve things far bigger than a European medal, things within themselves that will eventually push them to be world leaders, educators, strong parents and even world champions. It begins maybe with a failed uchi-mata and that is a noble journey.