A champion can thus be compared to a Formula 1 car, at the cutting edge of technology for sure, but also very fragile, like an inseparable corollary. Nobody likes injuries, that's obvious. While some may see some form of masochism in training for years, pushing the human machine to its limits, the pain of injury is never welcome. It suddenly interrupts a cycle of training and competition, always at the worst possible time.

Yet talking about a sprained knee or even a dislocated shoulder, is and will always remain easier than talking about a wound to the soul; this invisible wound that can capsize anything.

To speak of soul injury is an understatement that encompasses a whole category of problems encountered by high-level competitors. Too often we imagine them as machines, of which a bolt can eventually break, but which, whatever happens, will always have a mind of steel and an unfailing will. In our modern societies we don't talk about psychological wounds, we don't dare, we are afraid of comments and looks.

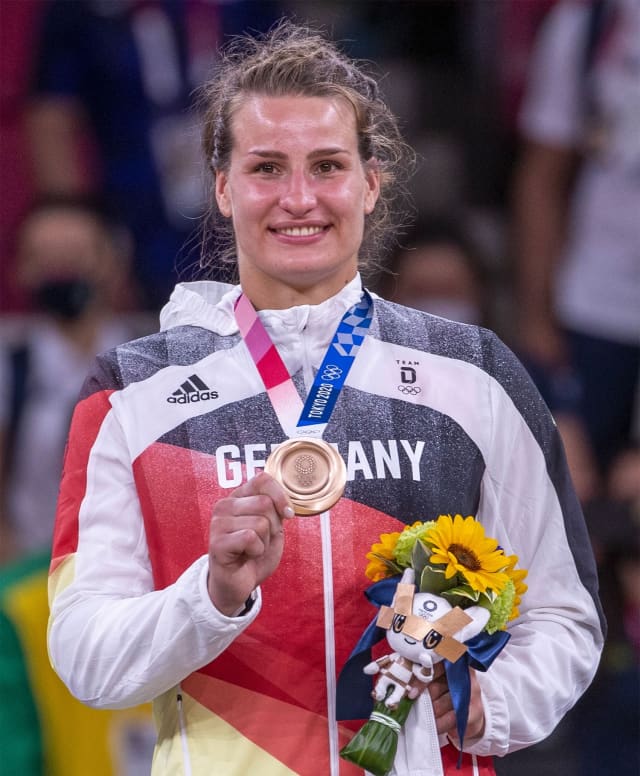

In this context, the testimony of Anna-Maria Wagner (GER) takes on an even deeper meaning. At 25, the judoka born in Ravensburg in the south of Germany, already has a flourishing record. World champion in 2021 in Budapest, she also climbed the Olympic podium in Tokyo, the one of the World Judo Masters in 2019 in Qingdao, nine times in grand slams and four times in grand prix. It is a fine track record, one that should make her smile all the time and yet, not everything is so rosy in the world of very high level sport and above all it is not easy.

Once again, it is not an equal measure of a winning machine to assume that one is always at the top of one's psychological form. If you really think about it, that should be obvious. If it is accepted that the body of an athlete goes through phases of highs and lows, why is it not the same with regard to psychology? Why aren't we talking about it? Without making inappropriate comparisons, isn't the brain also like a muscle or a joint, with its ups and downs?

For Anna-Maria, therefore, the post-Olympic Games period was difficult to manage, so much so that she wanted to put an end to her career, "I no longer wanted anything. I no longer wanted to talk about judo and I had even less desire to practise it. The Olympic medal was my childhood dream. I did everything to get there and this day of competition at the Budokan was almost perfect. For two weeks after the Games I was still in the same mood. It was quite exciting to live that period but suddenly, nothing, real emptiness, total nothingness. You have reached your goal and after?"

The question is not trivial and what Anna-Maria has experienced, others experience in silence, "I believe that we are role models for young people, especially when we win medals at the highest level. I want to let everyone know that we can all fall into this kind of depressive lethargy. I know it happens to other competitors but no-one talks about it, it’s taboo, but because I'm aware of my status as a world champion and Olympic medallist, I want to talk about it and tell them: no, this is all normal! There is nothing to be ashamed of and it should be talked about if possible. I know that it is too often a secret but I can tell you that talking about it has helped me a lot."

To talk about it is probably the best advice that Anna-Maria can give but to whom? "Often the coaches do not want to hear about it and for the public it is complicated to understand. How can a great champion have problems with depression? As for me, I have known for several years that even though I am a cheerful person, always smiling, I have moments, usually at the end of the winter for two or three weeks, when I don't feel well. It's just that, suddenly after the Games, it was multiplied but I was lucky to have an understanding coach and an entourage that didn't put any pressure on me. Everyone told me, ‘Take your time. Come back when you feel it and when you're at 100%. You're in no hurry.’ Many said it.”

Do not rush, talk about it freely and without fear around you. These are some keys to getting back on track. So that's what Anna-Maria does, "I know that if I'm at 100% of my ability I can beat anyone, but to be on top I also have to be 100% in my head. One does not go without the other. My mental health is just as important as my physical health. I want the public to know that this is not a disease and it should not be feared. I'm happy to have talked about it around me. I feel better and it helps me to 'roll the stone' a little more."

Roll the stone? The world champion decided to do it, "My decision is made, I don't want to stop high-level sport anymore and I want to work until Paris 2024, but for that I still have to find some mental energy. You know, the depression that I'm going through is not easy to manage. It's not a permanent state. I have very good days, even weeks and others where it's still difficult but it's better, much better. Maybe I'll be back in Georgia but that will only be the case if I feel able to win. Otherwise I'll take a little more time before getting back on the circuit."

At the moment, Anna-Maria has not quite regained the passion and above all the pleasure of training, but she feels in good shape. After more than six months of emotional yo-yoing, the great champion that she is already, has the perspective to analyse what happened to her, "As I said, it's a state that I knew because I had already experimented but only for a short period. After the Games I sank. I didn't want to do judo anymore but I didn't really want to do much anymore at all. I asked myself the question of whether the pandemic had some impact on that and I think I can say no, not directly anyway. I even think that Covid, because it put a lot of people in psychological distress, had rather a positive, revealing effect.” She paused to reflect further.

“It's a bit paradoxical but thanks to Covid, we were less afraid to talk about depression. What is certain is that the last few years have been very demanding. We were two German athletes in my category, for only one place at the Games. The pressure was huge and constant and this definitely had an impact on me."

Since she decided to speak, Anna-Maria feels even better. So it's certain that there are always days a little more complicated than others but the energy comes back little by little, at its own pace. The lack of motivation fades. The sadness flies away. The smile takes shape again on the face and the envy reappears.

"I really want to say that the coaches have to talk to their athletes and vice versa. You have to accept, you have to understand, you have to help. All of this is normal. Today I feel happy. A lot of people come to me to speak because they know that I did it. What I experienced can happen to anyone, to great champions even. You can, without realising it, find yourself in a depressive situation. It does not, should not, isolate you, even if the temptation is great."

What is certain is that Anna-Maria Wagner did not isolate herself. She spoke, she spoke to us and we are very happy because we too can experience similar situations. So the experience of a great champion who is not afraid of her challenges is a lesson for all of us and as she said, "Anyway, I'll come back stronger."