We introduced the statistics, the almost impossible feat and the question in our first article in the series, which can be found here:

https://www.ijf.org/news/show/151-olympic-champions-tokyo-to-tokyo

A reminder of the question:

It could be said that to be in the company of an Olympic judo champion is to be presented with someone whom has reached an absolute pinnacle, a ceiling which cannot be surpassed; there is nowhere further to ascend in the world of sport. We often find Olympic champions speaking with freedom and certainty, unafraid to share an opinion, speaking of their lives and paths with confidence. For many we feel there is peace, and that can be magnetic and inspiring.

So the question is, did they become Olympic champion because of that character or did they become that person having won the Olympic gold medal?

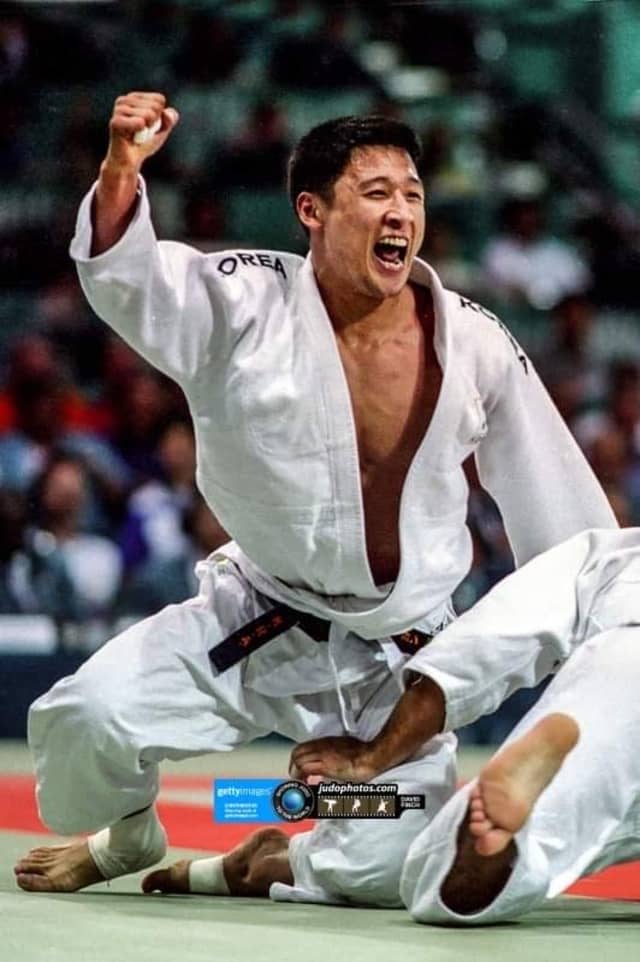

“I must thank my parents first because I have a very good natural physical condition due to genes. It was a good start!

From that point, I can say that since I was very young I really liked to win. I have a mind which likes to be challenged and always wanted to win, even in children’s games. At the age of 11 I chose judo from all that was available and I was so competitive from the beginning. I had seen a friend after training, with his judogi over his shoulder and I thought he looked cool. I thought if I tried judo I could look even cooler and I could maybe win at it.

From that moment I was determined and that took me to meet my fate but in my judo life there were a lot of difficult moments. It’s such a hard sport and in Korea the relationships with senior judoka and the hierarchical culture are so strong. This brings challenges.

Those moments could have made me give it up but my mother was my special reason to continue. The family religion is Buddhism. My mother always prays and she was so devout and committed before Atlanta, praying consistently for 100 days. 108 bows are required to deliver the message to the Buddha. She really wanted for me to become Olympic champion and I was motivated to make her happy. Her devotion to my success was really inspiring."

"When I trained judo at that time the economic situation was not too good and my family was not well off. In that hard period my mother still gave me everything I needed, despite difficulties. Her mentality is so strong and every time I am with her I still learn something new about how to live. She is still running a small restaurant but as an older woman this is very hard. She never gives up, still gives 100%.

In Korea there are bureaucratic systems. There is an invisible culture so that if a person doesn’t go to a particular university they cannot become Olympic champion but I chose not to go to Yong In University, the place I should go to with my objectives. Instead I chose to attend Kyonggi University closer to my home town of Cheongju. I studied there and trained judo there and so I broke the glass ceiling in Korean judo society. It was my choice and my parents supported me throughout. It is in my character that I am always learning but I also like to have choice and I never have regrets. I take full responsibility for my choices.

I think Olympic champions must be talented. They must also make a lot of effort, countless hours of training. When the athletes from my small university had to fight those from the Yong In University, it felt as if there was some level of bias, perhaps with a small score here and there or maybe a shido, which in those days could make the difference. It felt that I would not be able to get my wins without doing a lot more than would usually be expected. So, I worked harder; I had to throw for big scores. I had no choice. I liked to score ippon with seoi-nage. For my size I could have chosen different techniques such as uchi-mata but seoi-nage was my favourite."

"There were other aspects that contributed. When I was a young judoka, in the beginning, 99% of people were right-handed so I chose left. If I want to get past people I have to not just work harder but also in different ways and not be the same as other people. I think differently with strong analysis and harder work.

With specific regard to the question, actually I’m not sure if I would be the same person I am now without winning that gold medal in Atlanta. Earning a gold medal made me feel more humble in life, in some ways, and left me always wanting to learn more. I reached the summit of only that one thing but that only goes to show that it was only one strand. I must also be a respectable man always, so I have tried my best to be always humble and always positive.

Now I am a professor at the big university, at Yong In, in the Department of Judo, teaching both the theory and practice of judo, including history and all theoretical parts. I have a sports psychology PhD and I am sure it is all linked.”

In your mind was it possible not to win that medal?

“I had a fixed mind and I still do. If I set a goal, I meet that goal. I started judo and wanted to be Olympic champion and then I was. Then I wanted to be a professor and achieved it. I set a goal to work in the IJF team and I achieved it.

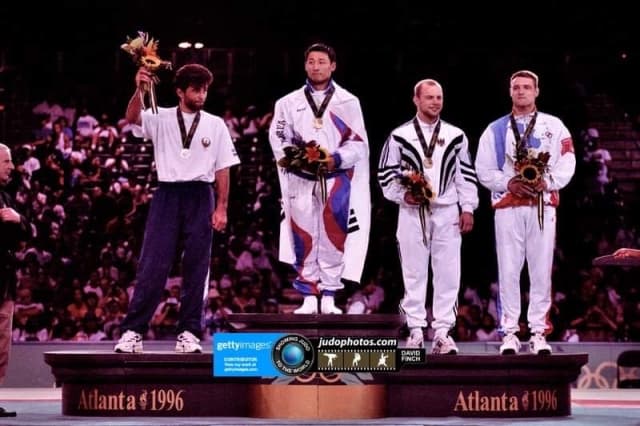

On the day itself, in 1996, maybe it was a little different and more specific. I had drawn Huizinga in the first round. It was the third time we had met that year. In February I met him in the semi-final of the Austrian Open and won with positive scores. Then in Germany some weeks later I lost to him on a shido. For our next meeting to be the first match of the Olympic Games, I was so nervous, I couldn’t sleep. I had just a couple of hours the night before my competition. The fight went to a yuko each and then hantei and I won it and so after the first round I was sure I would win the gold.”

Ki-Young Jeon’s answer confirms both sides of the question, that his character made him capable of being Olympic champion but that winning the medal shaped who he became and how his life moved forward from that point. He continues to be deeply involved in a judo life at the highest level, not only through his professorship but also as one of the IJF Head Referee Directors.