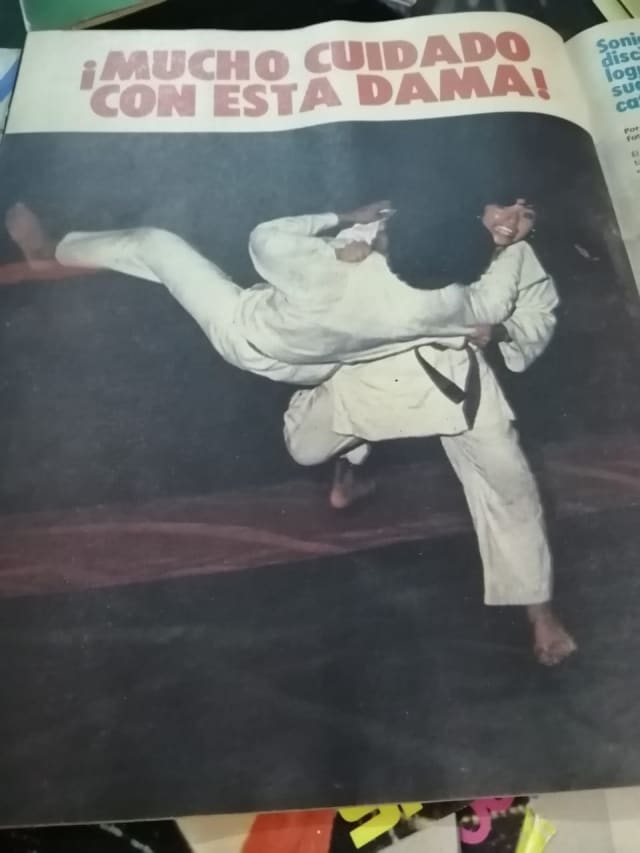

Sonia Carabajo was born in Guayaquil, into a family open to the world and to ideas of change and progress. One day, at her school, a physical education teacher gave judo lessons; nothing fancy, just enough to get the attention of Sonia and her friends. She was then 14 years old.

This was a revelation. What started as a distraction, something different and entertaining, turned into passion. Sonia met the one who would be her sensei, José de Sinavilla, the judo man in Ecuador.

The teacher immediately detected a special talent in Sonia's hands. She had to continue because the girl had potential. Sonia was able to go ahead because her parents supported her at all times and this is important, because Ecuador in the 1970s was a hotbed of machismo, where women with new ideas and their own will did not enjoy a good reputation.

“They looked at us badly, they thought we were tomboys,” explains Sonia. Still today, almost fifty years later, Sonia has a sweet voice and a singing accent. She speaks calmly, unhurriedly and her sentences sound like a melody even when speaking in a complicated context.

“I liked it and wanted to continue and compete seriously. Others quit earlier, they didn't have the talent or the vocation, but they tried and had fun. They all worked hard and learned to defend themselves."

Judo, at that time and in that country, did not ensure a prosperous future. This is how Sonia understood it, as a person who never stopped studying. In 1979 Sonia was victorious as South American champion, in Uruguay; a title that came at the right time because, in 1980, the first world championship for women was to be held.

“I didn't know, my coaches were in charge of signing up for tournaments. For this reason, when they told me that I would go to the United States, for me it was an earthquake of sensations."

Sonia had never been to New York. "It was like landing on another planet for me, the girl from Guayaquil, in the city of skyscrapers." Sonia was the only representative from her country. She traveled there with her coach, "excited about the challenge and about the responsibility of representing my country."

In a way, she made up for the athlete's loneliness with the unconditional support of those close to her. In New York she had relatives, uncles and cousins. "That helped me digest the moment and the anxiety."

It was three days before the serious business began. Sonia would be one of the first to wear judogi at the legendary Madison Square Garden because she belonged to the -48kg category. During those previous days she met her adversaries for the first time and what she saw was a shock.

“They were taller, wider and stronger. Some were even a bit masculine. I was very flirtatious and I made braids to include the flag of my country and took care of my appearance because I was used to being criticised in Ecuador."

Sonia understood that those other women had an advantage. They trained more and better and she even knew that the European women participated in international competitions and they had already fought each other before. They knew each other and they seemed very determined.

"I understood that I could not win, I was not up to the task, but I tried because, you know, judo is courage and determination."

Sonia lost her first fight against a British woman, whose name she does not remember. We do not want to remind her, so as not to force a story that flows naturally and in which she digs without effort, but without giving too much importance to some of those details. For her the important thing was to represent her country with dignity and all her femininity, in an historical event that would be the first step on a long journey towards equality.

“It was an honour to be there and participate. I would have liked to have had a higher level but I did not give up."

Sonia returned to her country and continued her life. She graduated from college and earned her medical degree in eye rehabilitation. She married and had three children. And judo?

“I stopped in 1985 when my first child was born. I didn't have time and, at 28 years old, I had to consider an equation and choose between my family, my job and judo. But I missed it."

Years passed and Sonia stayed away from judo. In 2017 she retired from work and today, at 63 years old, she looks back and speaks to us with the serenity that comes from maturity. So, now yes, she confesses a secret to us.

“Actually, judo was always inside of me. It helped me in the most delicate moments, when the danger was real."

Sonia was with her mother on a bus and a pickpocket stole her mother's purse. Sonia reacted, attacked and the result was a recovered purse and a scalded thief. On another occasion, another man, taller and stronger, tore a gold chain from Sonia when she was simply walking down the street. "I took off my heels and attacked." Sonia recovered the chain and the thief left without loot and with his honour tainted.

"Thanks to judo I was always in control, cold-blooded and always brave when conditions demanded it. In other words, I had self-control and courage."

It is perhaps the most relevant message. Life means making decisions and, in Sonia's case, moving away from judo to start a family and help others through medicine. It is also clear that life is not for forgetting, but for giving the best of oneself, especially when things get ugly. When that happened, when Sonia faced her fears, her nerves and anxiety, the danger of a physical attack, she did what she had learned. That has a name, it's called judo.