Today, Shayne A. P. Dahl is a cultural anthropologist at the University of Calgary, based in Alberta, Canada, where he completed his PhD after earlier studies at the University of Toronto. Alongside his academic career, he is a certified dojo instructor with Judo Canada and coaches at the Airdrie Judo Club, just north of Calgary, with the Canadian Rockies on the horizon. His coaching path has taken him across the country, from Saskatchewan to Manitoba, Ontario and Prince Edward Island, including time in historic clubs such as the Raymond Judo Club, the first dojo established in Alberta.

Judo entered his life early, around the age of eight, almost by chance. A local recreational centre down the street from his childhood home hosted a dojo. Friends joined, invited him along and what began as a simple activity became a defining influence. His first dojo was the Swift Current Judo Club in Saskatchewan, a place where the foundations of discipline, movement and respect were laid.

Since earning his shodan (1st dan) in 2009, following training in Japan, he has been involved in judo continuously as a coach and practitioner. Now in his forties, his relationship with judo has evolved; competition has given way to something deeper. Judo has become a way to maintain clarity of mind and vitality of body, while helping others pursue their own goals. He describes the dojo as a place where work stress disappears during warm-ups, where phones are forgotten in bags and where the balance of mind, technique and body (shin, gi, tai) is constantly renewed.

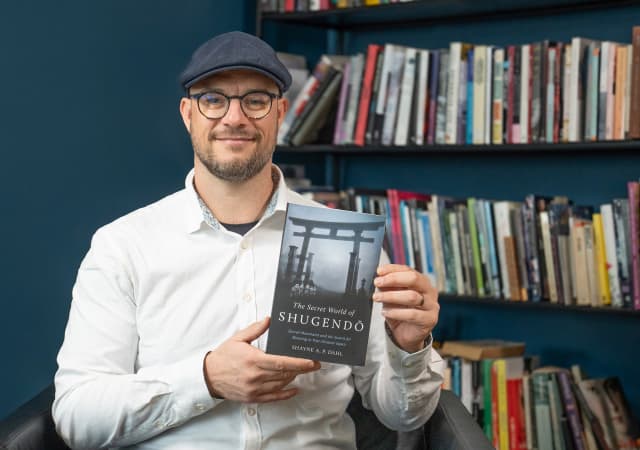

That renewal proved essential during the long process of writing his book, 'The Secret World of Shugendō.’ A decade-long academic project demands sustained focus and resilience and he is clear that without regular returns to the tatami, refreshing mind, body and spirit, the work would not have been possible.

Long before he chose anthropology as a career, judo had already set him on that path. As a child, he absorbed Japanese culture through movement and etiquette, learning basic Japanese terms, bowing protocols and respect for seniority, all before ever opening a world map or taking a social studies class. He describes this as a bodily form of enculturation. When he encountered university courses on anthropology, religious studies and Japanese history later on, judo had already prepared him to engage deeply with these subjects, both intellectually and experientially.

Those early encounters led to friendships with Japanese international students, one of whom would become his wife. Their meeting, he notes, would probably never have happened without his prior exposure to Japanese culture through judo. Today, they have two children and travel to Japan every summer to visit family, further deepening his connection to the country and reinforcing the link between his academic work and his life on the tatami.

At the heart of his daily practice are the two fundamental principles of judo, displayed prominently in his dojo: seiryoku zenyo (maximum efficiency, minimum effort) and jita kyoei (mutual welfare and benefit). Drawing on Kano’s writings, particularly Mind over Muscle, he explains that the highest level of judo is reached when these principles are applied to all aspects of life. For him, this means cultivating efficiency, perseverance and a commitment to work that benefits both oneself and society, values that guide his teaching, research and writing.

His years training in Japan, particularly in Mie and Yamagata prefectures, also shaped his understanding of judo’s cultural depth. While many dojo protocols have travelled internationally, some nuances remain tied to Japanese culture very closely. He highlights expressions such as onegaishimasu before randori and arigatō gozaimasu afterwards, small rituals repeated hundreds of times in a single practice, ones that embody respect, gratitude and mutual care. In his view, judo has been one of the most effective vehicles for exporting these values to the world.

Reflecting on Kano’s legacy, he points to the extraordinary journey from a small temple dojo, with a handful of tatami, to a global sport practised in the most remote corners of the world. Kano did not live to see judo become an Olympic sport but the lives influenced by judo across generations and continents form a legacy that continues to grow. That legacy extends even beyond judo itself, reaching disciplines such as Brazilian jiu-jitsu, introduced through Kano’s students.

Thus judo also played a central role in the writing of his book. His lifelong training prepared him physically and mentally for demanding doctoral fieldwork in Japan, which involved mountain ascents, waterfall meditation and ritualised practices. In many ways, he sees the book as the culmination of a journey that began with a childhood invitation to step onto the tatami.

When he speaks of a “judo-for-life” story, he challenges the idea that judo ends when competition does. While elite performance has its time, the deeper value of judo often emerges later. Around the world, countless recreational judoka lead their communities as coaches, mentors and professionals, carrying judo’s lessons into everyday life. The dojo, he believes, remains one of the few intergenerational spaces where elders can guide youth, where effort yields tangible progress and where advancing through belts mirrors progress through life itself.

In closing, he notes a gap still to be filled: the relative lack of research on judo despite its global reach. That gap is beginning to close with the IJf scientific journal ‘the Arts and Sciences of Judo,’ offering the possibility to researchers around the world to share their knowledge about judo. His own work, though focused on Japanese religion, would not exist without judo. He suspects many similar stories remain untold and that exploring them would reveal the full scope of Kano’s enduring legacy, one lived daily, quietly, by judoka around the world.