We introduced the statistics, the almost impossible feat and the question in our first article in the series, which can be found here:

https://www.ijf.org/news/show/151-olympic-champions-tokyo-to-tokyo

A reminder of the question:

It could be said that to be in the company of an Olympic judo champion is to be presented with someone whom has reached an absolute pinnacle, a ceiling which cannot be surpassed; there is nowhere further to ascend in the world of sport. We often find Olympic champions speaking with freedom and certainty, unafraid to share an opinion, speaking of their lives and paths with confidence. For many we feel there is peace, and that can be magnetic and inspiring.

So the question is, did they become Olympic champion because of that character or did they become that person having won the Olympic gold medal?

“Both of those things!”

This is an initial response many of our Olympic champions have expressed.

“My first good result was at the Hungarian Championships at age 15 but there was nothing much before that. The trainers didn’t think I was talented. I was tall and skinny and not really strong and my movement was similar to that of the English TV character Mr Bean. I have three children and the youngest who is ten has a similar build and physicality to how I was. I wasn’t so skilful and I also had pretty bad eyesight."

"The circumstances, my coaches, my brother, parents, friends all supported me to achieve. In my opinion it needed about 100 conditions to be right to become Olympic champion and only one of them was me. The rest of what was necessary came from others. I believe that if almost anyone was dropped into my exact circumstance and team they could have done it.

My coach was a very good judoka but had an accident in his earlier years and had to stop, so he arrived at coaching. If that never happened and he wasn’t my coach I wouldn’t have become Olympic champion. If my brother, who was 7 years older than me and much more talented, also didn’t give me the support that I had from him, it probably wouldn’t have happened. I had very good friends who always supported me too and that was invaluable.

I came from a very poor family, working in agriculture. When my father became sick I had to work a lot at home. I was only able to attend training camps when my friends could go to work at my house instead of me. There were so many conditions that combined to make this happen. Another example, there was a power plant built close to us that provided a lot of financial support too and had it not been built I may not have been able to afford my path to that medal.

I was only 20 when I won the Olympic Games and it was very difficult to manage. After that I needed a long time to understand why I was the one who achieved it. I am the only Hungarian to achieve that huge thing, right up to today. It felt as if there was a little destiny involved too but of course I also did my job! In my opinion though, my coach and support team were crucial. I had a very supportive club and although I was the only high level athlete there, I had friends who were living away from our town but who would come to help me train whenever I needed it.

My power comes from the team behind me. When I went to the tatami I felt always that this team of friends and family stood behind me pushing me to the contest. I wasn’t strong in technical terms like Inoue or the Japanese in general but I was strong in emotional and mental competence.

I was happy when I was young and just coming through. We were poor but my parents were a very happy couple always, until my father passed away. My father was 15 when he promised my mother that they would marry. My brother started his relationship with his now wife at 14 and I was first together with my wife at 15. My wife has always been supportive too. She is a very important part of this achievement.

You know, I had acne, bad eyesight, was skinny and weak but I always wanted to be the first. Any situation with a competitive element, I wanted to be first. Immediately that I knew it was a competition, of any kind, I became more focused.

I realised that I had to find my goals and once I had that in place I became determined; with a goal I could always fight a way to achieve it. Through my life, goals have continued to be important for me. It’s the same way I achieved my PhD. I wanted to be an engineer, following my brother but at that time it was almost impossible to do both academic things and sport well so I made a break from study during the Olympic preparation. I didn’t want to not finish it so even though my life took me to a PhD in economics, I came back to that first technical university qualification eventually and completed it just last year.

When I was a young boy I started a lot of things and gave them up but my coach said that if I have the chance to achieve something special, I should continue, I must do it. He was key to changing my mindset. He taught me to find challenges and work to solve them."

"French novelist, poet and playwright Jules Verne wrote that if we are afraid of something we must do it immediately. My coach was similar. He said you look for danger or fear and then you must handle it. That is why I started to commit to things both inside and outside of judo. I achieved confidence because I tried a lot of things and didn’t fear failure; I committed.

The phrase ‘Do or do not; there is no try,’ is attributed to Yoda. I think this is partially right and that you must try with full energy and if you are not successful you must try again and again and again.

In my judo days, there was also Akos Braun in the team. He and I competed against each other in all sorts of things, maybe running or press-ups or something else but neither of us would give up against the other. We always wanted to win, with stubbornness and also always with good humour. Our coach had to stop us sometimes because he knew we would never give up. That is also a version of competitiveness and commitment.”

Did the medal change you?

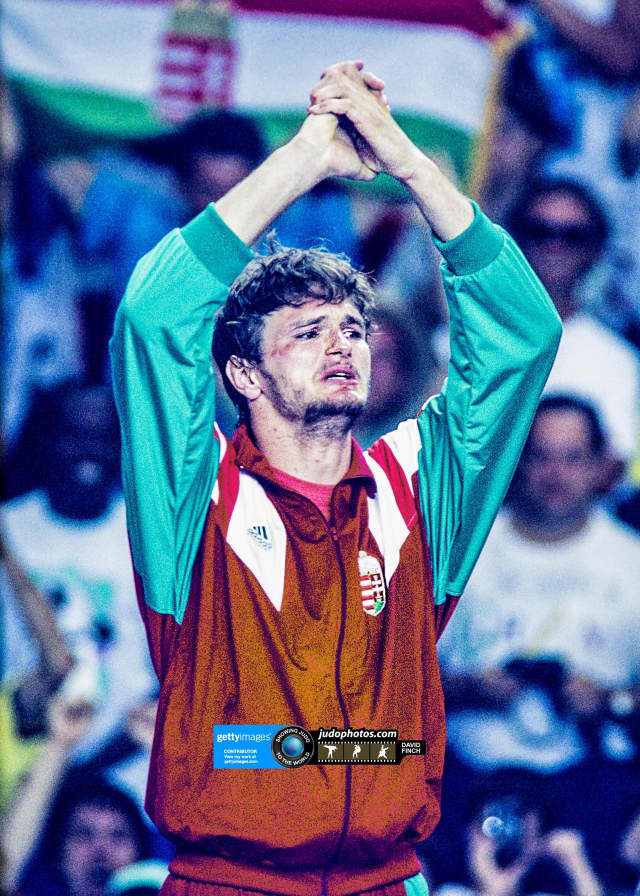

“The medal changed me, of course. Before the Games I looked at Olympic champions as demi-gods. On my day the fights just sort of went. My coach always told me just to focus on what was exactly next and I did, one fight at a time, only being free to be happy at the end of the day. After each fight I would look for the next. When I won the semi-final I had the minimum of silver and everyone wanted to congratulate me but I didn’t want that because the day was not finished. How dare I think that silver is not enough but I had to put down that feeling of ‘the minimum silver’ and focus on the final. When it was over there was no reason to push that feeling down anymore. I felt something amazing had happened, something almost impossible. Afterwards, sometimes I would wake up and not quite know if it was real. I couldn’t really absorb it, what I had achieved.

After the Games I took 18 months to really believe I was the champion but to tell the truth in full, for example, I was standing between Mr Hosokawa and Mr Ono at the draw of the 2023 World Judo Masters and I was not believing I should be with them. It is still difficult to really understand what I did. It’s still very emotional for me. I sometimes meet Mr Yasuhiro Yamashita who was always a hero of mine. He is at the very top and he knows my name when we meet. I feel so much respect and emotion.

After the medal the responsibility was so high. Before the Games I was an average young man, was joking with friends. After that I had to behave in the right way, on the high level. Before, if I had a bad mark at university, it didn’t matter, but after the medal I became someone who never allowed myself to be ill-prepared. I was afraid the teachers would say that I am expect a mark because I think I’m someone. Instead of risking that, I do all I can to be correct. It’s such a responsibility. I became suddenly and icon for local children, who maybe started judo because of me. I tried to hold that high level of personal accountability through my life from then. I keep that approach."

"The medal is in the past but I try to always behave, ever since, as if I deserve that medal. I want to give back. In my professional working life I achieve things and I have a lot of success and so with judo aswel maybe it’s possible to say I am a successful man but I must give back to judo and I only ever do that as a volunteering.

I’m never so happy and satisfied and calm as when I am at judo, either at an event or meeting old judo friends or in the local dojo at home. All my friends who grew up with me, support their children through judo. They realised how it built me from this skinny, weak guy into a successful man.”

There are many areas of his life in judo which Antal Kovacs believes transferred into his life after competitive sport.

“In judo if someone did a seoi-nage against me twice, I would go home and study how to fix it. I did this every time. Immediately I leave the tatami I am thinking about how to correct my mistakes and this is applied in my everyday life too. I know my goals, am not aggressive but I am assertive. We don’t push other people out of the way, no, we work on ourselves for the victory.“