You have to imagine that at the end of the 19th century, judo was still largely unknown; it was only in its infancy. Although the attraction for Japan, which was opening up, grew every day, judo was totally unknown in Europe and obviously in the rest of the world. However, Kano already had a very precise idea of what he wanted to do with it. His return trip to Japan, during which he stopped in Egypt, offered him the opportunity to affirm some technical and philosophical principles which still play a crucial role in the development of modern judo.

Once again, what attracted Kano to Cairo was above all curiosity. Quite simply, not wanting to take the same route on the way back as on the outward journey, Egypt and its archaeological and cultural riches were too tempting for the young man. Accompanied by an Englishman, a Frenchman, a Dutchman, a Swiss and an Austrian, he set off to explore the city and then the pyramids.

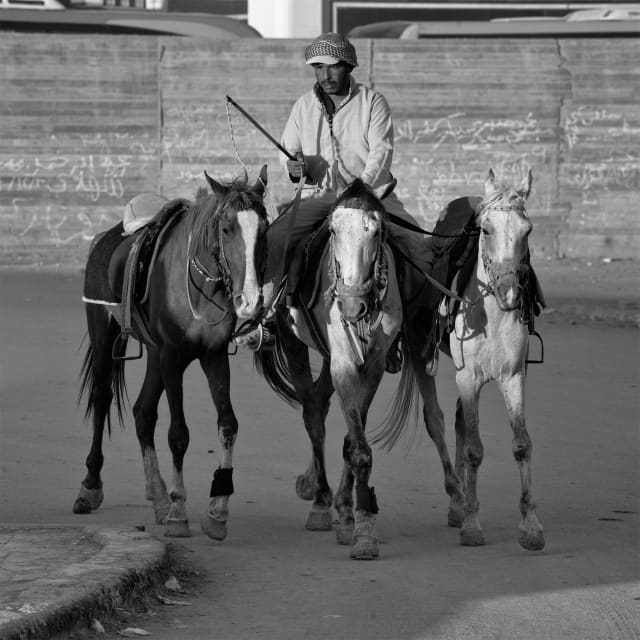

Kano wrote in his travel diaries, "In the evening we visited the whole city of Cairo. With the streets being covered with stones, we decided to ride a donkey. I had already experienced riding a horse in Japan but as I was not very skilful, I felt a little apprehensive about travelling on the back of a donkey, trotting on stony paths. I discovered many things." (source: Jigoro Kano, Father of Judo - Michel Mazac - Budo Editions, 2014).

The next day, it was on the back of a camel that Jigoro Kano set off to explore the desert surroundings of Cairo, particularly the Sphinx and the pyramids which he began to climb. He took great pride in having been able to climb alone, without help and without needing to rehydrate. Kano explained, "As we approached the summit, our guides offered us water in an earthenware container resembling a sake jug. Long accustomed to not drinking, from judo randori training, I refused. When we arrived at the top, the sun was just beginning to rise, it was an indescribable landscape. The fact that the ascent went well demonstrated my very strong determination and the efficiency of regular training. It was an interesting experience." (source: Jigoro Kano, Father of Judo - Michel Mazac - Budo Editions, 2014).

Unfortunately Kano did not have time to delve deeper into ancient Egyptian culture. He had to get back on the road, or the train and then the boat, to be more precise. He stopped over in Aden, then a part of the British Protectorate of Aden, now in Yemen. He then crossed the Indian Ocean and arrived in Colombo in Sri Lanka, before reaching Saigon, today Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, and later Hong Kong. Kano took advantage of the long ocean crossings to demonstrate to the other passengers his skills in combat sports and therefore in judo. He gained a certain notoriety and sincere respect from it.

His demonstration of judo was performed at the expense of a naval officer present on the ship and whose strength was legendary. During a friendly challenge, Kano was able to hold the sailor to the ground, while the latter failed to block Kano. This used one of the principles on which he had worked, consisted of using the force of the other and to return it against him. Impressed by Kano's agility and strength, despite his small stature, the passengers asked him to demonstrate some throwing techniques, which he had told them about.

The officer who had been defeated on the ground by Kano and who was a little upset, asked him to try to throw him. The two men agreed on a formula which consisted of a fight where the winner would be the one who threw the other. Kano explained, "The officer crossed his hands behind my back and did his best to knock me down, swinging me right and left.

I suffered this once or twice; I was waiting for the right opportunity to enter my movement and soon, at the right moment, I threw him with a form that was half koshi-nage, half seoi-nage. It was obvious that the head was going to fall forward, so I quickly supported his head so that it didn't hit the floor." Kano had just demonstrated the effectiveness of his judo, but also his respect for the partner. The officer and Kano became good friends for the rest of the trip.

During his journey, Jigoro Kano never stopped discovering local customs. His curiosity had no limits. He wanted to know, he wanted to learn, because he had a feeling that somehow the cultural wealth he was storing would come in handy sooner or later. A man of great knowledge, he liked to share it, but he was also particularly fond of blending into the crowd to perceive the essence of the world.