Seeing our sport develop on healthy foundations is already a victory in itself, on the way to establishing a more just society. But is it enough? Can and should we be happy to simply bow when we enter the dojo, or at the start of a randori, to show respect? Is that enough? To ask the question is to answer it and the answer is obviously no.

Before understanding what is hidden behind this term, which tends to be overused or used incorrectly, it is important to understand its meaning. Respect can be defined in the first place as a feeling of consideration towards someone, that directs one to treat him/her with respect.

Some show consideration or esteem, others go so far as to associate piety and reverence. Are we not talking about respect for the dead? In this sense, respect takes on a sacred dimension, but it is also possible and often necessary and even essential to have respect for things or places, even for actions. Respect is therefore no longer focused on a person, but on our environment and the actions we take.

We are more often wary of the opposite of respect, which can be characterised by casualness, impertinence or even insolence, disrespect and irreverence, but we do forget to look at ourselves in a mirror sometimes. Doesn't respect start with yourself?

For us judoka, who enter a dojo, it is obvious that we respect the place of practice first, by keeping it in a good state of cleanliness. We then respect the word of the teacher, the coach, our sensei. We also respect our training partners and later our opponents in competition. Without this sacrosanct respect, the practice of judo would simply be impossible and would not even exist. If we do not pay attention to our training partners, it will not be long before we find ourselves alone because no one will want to do judo with us anymore, hence the importance of retaining our partners when they fall.

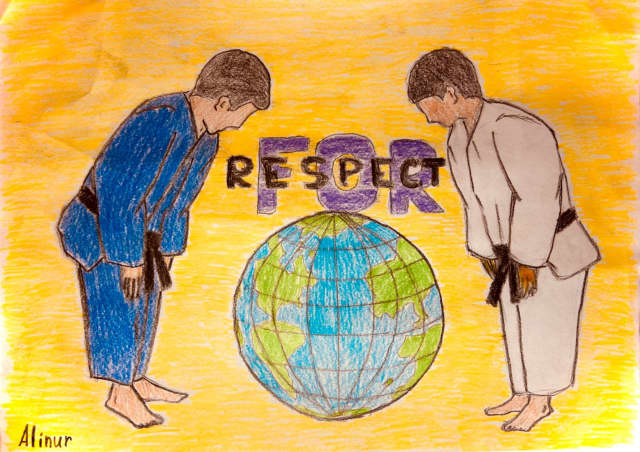

Despite our sport apparently being an individual sport, it can only be practised in a group (at least two) and for that, respect is then on-negotiable absolute. There is no doubt that the bow, the ultimate symbol of respect, is only the visible part of it, because it must be reflected in each of our actions. Practising judo is therefore not limited to what happens on the tatami, because respect for others outside the dojo must be exactly the same. It is important to respect your political or professional opponent. It is crucial to respect your life partner, children, parents, colleagues, friends. In the current period of confinement, where it is difficult to practise on a tatami, each judoka can and must therefore continue to 'do judo' mentally and philosophically.

As we said earlier, respect begins with yourself. If you do not respect yourself, if you do not take care of your body and your mind, once again, you will soon find yourself alone in the middle of an empty tatami. The French author Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) said: "We respect a man who respects himself." While George Bernard Shaw, the Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist explained: “No man who is occupied in doing a very difficult thing, and doing it very well, ever loses his self-respect.”

Let's take a step back, to better understand what we are talking about. Respect draws its etymology from the Latin term 'respicere' which means 'to look back'. This could be interpreted as the ability to understand what has been said and accepted in the past in order to draw conclusions and consequences in the present. On this etymological basis, we can speak of respecting the word given, respecting an agreement or respecting the rules of a game or sport. We are talking about the ability to remember all those moments during which we are committed to keeping a promise, meeting the conditions of a contract, or complying with the rules of the game.

When we apply these principles to ourselves, respect takes on a dimension that is close to self-esteem and the ability we have to remember our actions of the past. It is an important nuance, however, because respect takes on a completely different turn when it is confused with tolerance. This does not have the same motives and is not incompatible with contempt.

Under the pretext of tolerance we sometimes forget that actually respect implies accepting, whether it is the acceptance of the other or the acceptance of oneself, which is not necessarily the least important or easiest thing to do. Sometimes an excess of misunderstood respect can also lead to historical nonsense: in the Middle Ages, under the pretext of literally respecting sacred texts, the inquisition pursued all those who did not think 'as it should be'. This drift has been noted and can still be seen in all areas where a dogma is erected in immovable value. However, respect is neither a dogma nor a religion.

From antiquity, then in the Middle Ages or in the Age of Enlightenment, and more generally since humans began to live in society, the concept of respect has been developing. If it has evolved over centuries, there is a common base, which means that even if judo was invented in Japan, in Asia, the values it conveys are transferable and understandable across the globe.

For the German philosopher Emmanuel Kant, respect is a human concept that only applies to human beings. Yet as soon as we put on our first judogi, at first without really understanding why, we accept that respect is due to all that we are, to everything that surrounds us and to all those with whom we live and interact.

It is important, nevertheless, not to go overboard and this is what the French philosopher and writer Albert Camus explained, “Nothing is more despicable than respect based on fear, thus giving respect to establishment, a less dignified and paradoxically 'less respectable' aspect of respect".

If we must respect the other, we must also respect their values and differences, without any discrimination. This is a fundamental ethical value of our sport, even if there are different scales of values, depending on the civilisations, societies and even social groups which constitute it.

In its social dimension, respect is therefore above all human, based on what each of us must or should experience towards any of our fellow human beings. We symbolise this human respect by the bow and this is the reason why it must not and should not ever disappear from judo, or we'll lose our soul and we will no longer be able to create the conditions required for the development of a fairer society. If respect has disappeared massively from the relationships that exist between people, this is not a reason, for us to in turn lose it.

We can and must therefore associate with respect, politeness, one of the other strong values of the moral code of judo. Respect and politeness create the soil necessary for the harmonious growth of the individual and the group. It is also up to us to extend the idea of respect, to the elderly, the dead, minorities, the weakest, privacy, human dignity and nature as a whole. This runs through education and it is for this reason that judo is a fantastic educational tool for everyone, young and old.

This is what the American author William Burroughs summarises by saying, “The aim of education is the knowledge, not of facts, but of values”, or what the British author Laurence Sterne completes by explaining, “Respect for ourselves guides our morals; respect for others guides our manners.”

Judo’s founder Jigoro Kano said, “Before and after practicing Judo or engaging in a match, opponents bow to each other. Bowing is an expression of gratitude and respect. In effect, you are thanking your opponent for giving you the opportunity to improve your technique.”

These few explanations allow us to understand that what we do in dojos around the world amounts to recreating, in a restricted area, the conditions for the development of societies on our planet. No judo club can function in the long term if respect for self and others is not established as a basic rule. No judo club can survive if respecting the place and the words given are just spoken without absorption. No judo club has a future, if we abandon the bow, because it is through it that day after day, we teach ourselves and our children, that respect is the essential condition for creating trust.

All illustrations presented in this article were submitted by children for the Great8 Contest. Sumbit your own drawing at: CLICK HERE