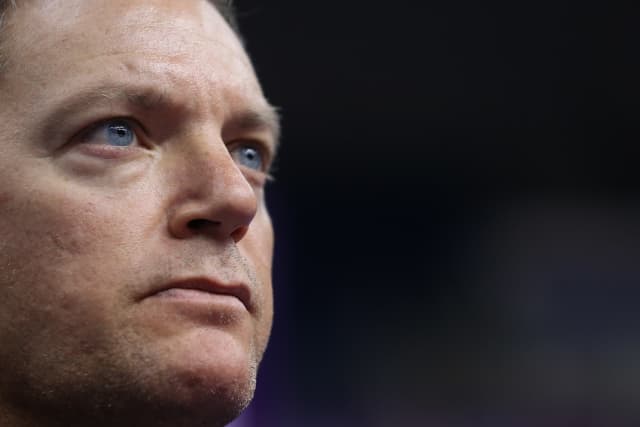

Shany Hershko is not afraid to be seen; Israeli national coach and avid supporter of every athlete in his charge. He is known the world over as Yarden Gerbi’s coach. The -63kg star won an Olympic bronze in Rio de Janeiro in 2016, but is most admired for her incredible performance at the 2013 World Championships where her innovative ne-waza took her category by surprise. A world silver the following year planted her solidly as one of Israel’s finest ever athletes, across all sports.

A cloud of inspirational wisdom surrounds Shany. There is always energy and passion and sometimes a child-like mischief. It’s magnetic and intimidating simultaneously.

He knows that despite being born in Israel, his journey didn’t begin there. His heritage and the course of his ascendants’ lives is firmly rooted in the upheaval and darkness of the Second World War Holocaust. His mother was Hungarian, from a wealthy family living in Budapest and his father was Romanian. Both families, Jewish, had to migrate to stand a chance of survival.

Shany’s father was ten years old when transport for all Jews to the concentration camps became inevitable, but he cheated the system and took a train to Bulgaria, meant only for orphans, and then jumped on an illegal boat out. He travelled alone and lived in a Jewish refugee camp in Cyprus from age ten to twelve without any family around him. A group of children then travelled to Israel together and after two years or so alone there, he was reunited with his parents. He never spoke of the years he spent as a child alone in war-torn Europe.

Shany’s mother spent her early years with her own mother, being raised in a Christian area of Budapest, avoiding trouble, while her sisters struggled through the horrors of Auschwitz and survived, miraculously. Eventually the family moved to Israel and we can begin to understand Shany’s own loyalties and gratitude for life; a product of such strong people.

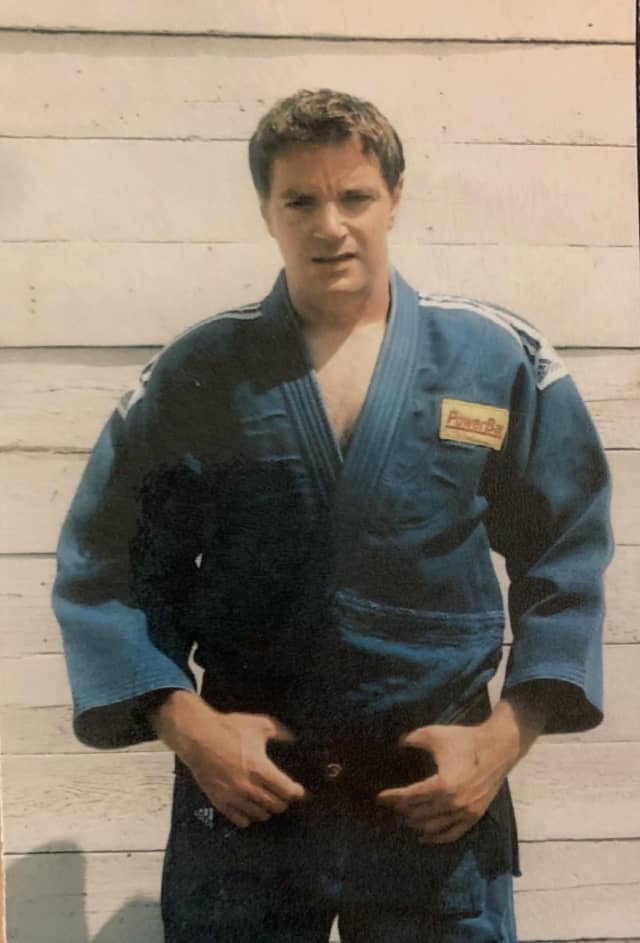

Shany’s judo journey began at the age of 6. “My neighbour said to come. After one year he quit and I stayed. I have no memories before judo!” He trained and improved and made his way on to the national team. He worked towards Olympic selection but admits to not quite being good enough. Coaching followed naturally and so he set his mind to being the best coach he could be. As a young man he didn’t seek a career outside of judo and he didn’t forge an academic pathway, just judo.

“I have only been in judo forever. So now I am at university, studying a bachelors degree in sport education. After Rio the school for sport in Wingate, the national sport centre, really tried to support the coaches. Wingate is also using us for research in talent ID.”

Shany is enjoying the challenge a formal education brings but notes that for him it is necessary, even with academia behind him, to trust his own feeling as a coach, to combine science with instinct. He is a self-confessed judo nerd and loves to find the trends and statistics that judo emits. They back up and inform his coaching practice. Ask Shany any question about statistics and he sparkles and rummages through his saved articles and graphs on his phone.

“I’m looking forward to giving a lecture on judo statistics in Tel Aviv, in a multi-sport education conference. I love statistics! For example, Sasson and Yarden were only the second time ever that Israel took two medals in one sport at the Olympic Games. The previous time was also judo, but in 1992 with Yeal Arad and Oren Smadga."

“My favourite memory? Winning the world championship with Yarden, has to be. Just ten days before we almost cancelled participation because she fell and injured the collar bone. She didn’t train for ten days and at the last minute we chose to go. One of her best performances ever. Every fight won by ippon in a different situation. Only with Clarisse did she have to score twice.”

“I’ve had the honour to be with her from when she was little and have found that always the best place for her to make a good result was when she had the hardest challenge, like beating the Japanese judoka for the bronze at the Olympic Games or the semi-final of worlds. In Rio the only Japanese fighter to lose a medal fight was Toshiro, losing to Yarden for that bronze medal. I like statistics!”

When asked about his worst day in judo he smiled and thought carefully, a really long pause, “It still didn’t come, I think! I never think about this. Last world championships in Tokyo was bad. Of course it doesn’t feel good, but there are always many things to take from it. I try not to think deeply about the bad days. When athletes get injured, these days are always bad.”

He continued to talk about injury and recovery and how the team responds to challenge. “I feel the symbiosis of the relationships is very powerful. When they give me 100% I want to give them 100%. Sometimes when their competitive journey is finished I love them more. To love them too much during the sport journey can affect the job, like when you love your children too much and you let them get away with naughty things. Too much emotion maybe is a danger.” Shany is proud to call many of his former athletes friends now, none closer than Yarden. What they shared on their judo path was unique and very special.

We discussed the current Israeli team and their future and Shany smirked, “I Like to have fun creating stressful situations with the athletes so that once they have overcome these stresses they can manage the minor stress of competition. I try to force them to have arguments, to study life, to debate.”

He becomes a little more serious and says quietly, “My coaching style is also to give them history and culture. I have a responsibility to prepare them for living outside judo someday.”

This wholistic approach and genuine duty of care is what binds the judoka to him and create the sincere trust and togetherness that we recognise all too well on the Tour. Trust is very important to Shany, in all aspects of life.

“It’s part of why I love Japan, it’s like a different galaxy. There is trust there, anywhere and everywhere, always treated with respect. I like the freshness of the food and am never scared to destroy my stomach!”

Looking forward to the Summer Olympic Games and beyond, he is excited about his team’s potential in Tokyo, but reflects on his own part in that and in the team’s years beyond 2020.

“I think national coaches must have a time limit. I would love to stay around judo and sport in general and I think I have some good years still ahead in role, but not forever. For the next cycle I think I will have the best team ever and they really excite me. Paris can be the best Olympics for Israeli judo. But I will let the future take me once I am not a national coach. After Paris I can’t see the future at all. I’m in its hands.”

“Luck is something that belongs to the one who works hard, so I am not afraid of whatever comes next.”

Shany and the Israeli judo team will be under the spotlight in the coming days, as the draw is unveiled and the first Grand Prix of the year gets underway, in Tel Aviv. Catch it all online via the IJF website.